Yikes: My Two-Cents on the The Zen Sex Scandals, published by the Weeklings

Some Personal Reflections on the Most Recent Zen Teacher Sex Scandal

IT WAS SPRING. I remember that. It might have even been Easter Sunday, the day after our brunch, when Dena called me. She was the wife of my almost ex-boyfriend’s best friend, and I had gone to their house for quiche and company on Saturday morning. I was terribly lonely, anxious and confused. I remember hanging out with them and their rabbits, and talking way too much about myself, my drama of one, asking the ridiculous Why? Why? Why? trying to sniff out clues about the man I so desperately longed for, and whose on-again/off-again attention, affection, and rage, among other things, were killing me.

Though still pretty bona fide nuts, I had also begun practicing, of all things, Zen. Big time. One of many surprises. And I was throwing myself into it with a passion heretofore reserved for self-destruction. It had never, not once in my 20-something years, occurred to me to seek a spiritual solution to the overbearing problem of myself. And yet, the first time I ever sat perfectly still for three minutes of zazen, the Buddhist practice of sitting with what we might call “Reality,” it was like a puzzle piece snapped into place. I saw how dearly I had been dying for a depth of experience that I could actually feel in my own body, alone, and how a lifetime of flailing had been for naught.

Everything was a shock to me in those days. The fact that I was still alive. The fact that I began sitting still on a cushion for 30-minute chunks. The fact that I was rising from these periods of zazen with a lightness in my chest I could only call happiness. It was all so…unexpected.

Another surprise was Daido, the Italian-American, Jersey born and bred, tattooed, 60-something, Zen teacher who I first spotted standing all lanky and bad-ass in the middle of the Zen Mountain Monastery dining hall, surrounded by minions, smoking a cigarette. And the way he sat in his dokusan room, the place where teacher and student have their ritualized, yet real, private meetings, his huge, brown, animal-like eyes soft and open, seeing me, teaching me, step by step, how to stay in my body as I took a breath. How to let go of a thought, gently. How to sit through the storms that rocked me. And when he felt it was time, he would reach for his brass bell, ring it, and I would get up off the floor where I had been sitting on my knees in front of him, put my hands palm to palm together in gassho, do a standing bow, and wordlessly wait for the next person to open the door. When he or she arrived, we would silently bow together, all the while Daido still sitting on the floor, legs crossed beneath his robes, eyes lowered, awaiting whoever came next. And I would return to my place in the zendo. What the hell was going on? Who was this guy? Who was I? I had no idea, but I was developing an interest in questions that felt much more promising than “Will he call today?” and it was thrilling.

So when Dena phoned to alert me to the fact that Daido was having sex with his female students, another surprise occurred: I, for no good reason, didn’t believe it. We went through the details, me saying, No way. Not Daido. And her saying, Yes way; Yes, Daido. She was insistent. Isn’t that monastery of yours in the Catskills, she asked. And I said, Yes. Well, she said, my friend who writes for Tricycle Magazine, a very trusted source, said everyone knows, the Zen master in the Catskills comes on to his students and has been doing it for years. It’s a fact. I wanted to feel like Dena was trying to protect me, and I suppose she was, but I also got my first taste of what I now know so well, that Gotcha! energy of people looking for the crack in religious devotion.

Turns out, my faith, my felt-sense experience of Daido, was right on. The Zen Master Dena was referring to—correctly, I might add—was Eido Shimano Roshi, Abbot of Dai Busatsu Monastery, also in the Catskills, ironically one of Daido’s first teachers. And while there are certainly shared elements between Daido’s Zen Mountain Monastery and Eido’s Dai Busatsu, there is also much that is different. Without getting into all the technical aspects of different schools of Zen, etc., etc., it’s important to note that both part ways with traditional Zen training halls and allow men and women to practice together, but Daido, even though he became romantically involved for many years with the first student he empowered to teach, did not make a habit of going after women in training with him.

In fact, many of us who were young women at the time felt a particular kind of gratitude to him for allowing us to let it all hang out, to be so emotionally open, and to be taken in in the kindest way possible, as Buddhas, for Christ’s sakes. Now, let me say this: Daido, who died from cancer in 2009, was not a saint. He could be controlling, arrogant, and short-sighted. But he was not doing that. And I knew enough about sexual power and abuse to trust my spidey-sense, even when presented with such irrefutable evidence to the contrary.

At least that’s how I like to frame the story. Lord knows there are plenty of other potential outcomes. Some even make news.

On February 11, 2013, the New York Times published an article about the latest version of a long and drawn out series of accusations of sexual abuse on the part of the 105-year old Joshu Sasaki Roshi, the Japanese Zen teacher made famous by the fact that Leonard Cohen studied and lived with him for many years (which, to me, pales in comparison with the fact that the guy is 105!). The piece was called, “Zen Groups Distressed by Accusations against Teacher,” which was a little misleading. I mean, yes, we are distressed, but not because we are just learning that Sasaki has been “groping” his female students for decades. We’re distressed that the craziness is still going on, and that an absurd number of Zen teachers, as well as the most beloved of our Tibetan teachers, have kicked up a sex storm in some way, shape, or form. Some long, involved, predatory and truly sociopathic; others more aw, shucks, I fell in love (again) with someone who trusted me, and oops, I happen to be married (for the 2nd or 3rd time); others are just your garden-variety tantric fuck-fests among consenting adults, except for the occasional (exceptional, of course) teenage girl. And then there are cases of basically appropriately matched and available people really wanting to be together and trying to make it work, even as they deal with the consequences of riling up and possibly confusing their community. I think that’s what happened with Daido and his student, though, I guess, I could be wrong. In any case, it’s kind of interesting, the way hearing about all this sex is kind of pornographically boring. Like, ok people. We get it. Affairs of the heart (and other regions) are powerful. We’re complicated. Nobody’s perfect; we’re all human, and genuine abusers need to be treated as such, unveiled from the shroud of Zen magic. Jail? Disrobing? Public Shaming? Maybe. But in order to choose the appropriate punishment, I think it’s only fair that we consider the nature of the crime.

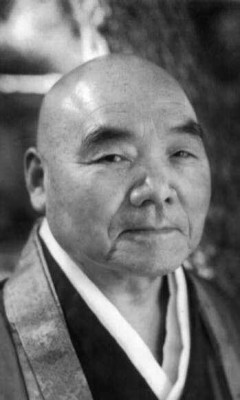

Joshu Sasaki Roshi, his mentoring of Leonard Cohen has been overshadowed by a long history of sex scandals.

In the context of daily reports of Catholic priests ruining lives, not to mention a million other horrors committed in the name of some mystical calling, it’s easy to want to shut religion down entirely. These priests are lost and repressed and victims themselves of an out of touch set of teachings. And they are given way too much power. Clearly, it’s not working. One could say the same about Zen, that all this devotional hogwash is a good-for-nothing holdover from a more primitive, or, at least, very different, time and culture. Who needs the whole Buddhist thing anyway? Maybe just a good dose of mindfulness would do the trick, and soothe what ails us. Or some combination of Western psychology styled up with up with a dash of Zen flavor might satisfy our craving from some deep Eastern wisdom, but allow us to keep our distance from the danger of getting so mixed up in one of these weird teacher-student things. And it’s true: working with a teacher is not safe.

But I’m left with questions like: How can we expect to break through the tenacity of our thinking minds if we aren’t willing to take a risk? A big risk?

With that said, how can we break through when we’re under threat?

And what exactly is it that needs protecting?

Sometimes, when the Zen-sex-scandals news cycle rears its ugly head, as disturbed as I am about it all, I also kind of shrug it off with a slight sniff of superiority (true to my teacher, after all) because it hasn’t happened in my direct community, though you don’t have too look too far back our 1st generation 70’s hippie Zen past to find plenty of references to the, “it’s complicated” routine. In any case, when this most recent version about Sasaki appeared, and my Zen friends started shooting emails back and forth, trying to come to terms with this…again…..I was a little numb to the whole thing. But then one friend got me when she wrote, “We sound like a bunch of cult-y imbecile children when the mainstream press writes about us. It’s kind of maddening.” I agreed with her, that we do sound like that, but I had a scary thought at the same time: We kind of act like that! And I wondered why.

So I decided to write about it.

Before turning this piece in, I had a few restless nights, afraid, really, that I was breaking some rules of Zen—stated and implied—and maybe even some grave

precepts. And I wondered how to navigate my desire to tell it like it is, from my

very personal point of view, continue to work with the edge of my flaring ego,

be confident in my experience, but not be attached to “knowing,” all at the same

time. And most importantly, how could I help readers appreciate a little taste

of the nitty-gritty, while still honoring my teacher? Because the thing is, in Zen,

the teacher-student relationship is as sacred as it gets, and essentially private. I

know that might sound creepy, but it is held in this way as a means of protecting what happens between the two, which is very specific, subtle, personal, mysterious.

Sharing it with others can kill the potency of what the teacher is offering, as well

as confuse the other student being shared with, as in, geez, he never says that to me! And I agree. As a rule of thumb, keeping what happens between me and my teacher quiet is the right thing to do. But the downside is obvious.

And so it seemed like a good idea, in light of all this press about the sicknesses of different religions, to share open a tiny window onto what it can be like when it’s working well. As strange as it may appear.

Over the years I have had many dreams about Daido. In them, we are either together, say, deep-sea scuba diving, or just sharing a meal; other times I dreamt fantasy replays of, or improvements upon, some unsatisfying interaction; other times he was just a bit character in some unrelated drama—the usual nightly fare for most Zen students, I imagine. However, at one point during my two years of living at the monastery, I had a series of very powerful dreams about him, the kind of dreams that are still alive, here at my desk, all these years and lifetimes later. They were dark, and he was always just around the bend—on the other side of a door, or waiting for me down some long, dusky hall. And he wanted me. Bad. And the feeling of collapsing into his arms, the total, whole-body-mind cosmic glory of his loving me and only me was a complete merging of the universe-wide, soft bliss of zazen, with the other kinds of aching pleasure that come from bodies in this life, if we’re lucky. I would wake up from these dreams a bit flustered, but also knowing—a deep, crazy knowing—that this was not about Daido; this was a dream of God loving me.

One reason often cited for the ready-access to abuse among Catholic clergy is their role as intermediaries between God and us. A Zen teacher’s empowerment to teach doesn’t come from God, but from their teacher, who was empowered by their teacher, and so on, going back all the way through Japan, China, and finally to India where Shakyamuni Buddha first passed the baton 2500 years ago. So there is some similarity between a Zen teacher and a Catholic priest in that they are both closely aligned with the primary religious figure of their tradition. However, in Buddhism, that primary figure is not a supernatural all-knowing power-source, but the Buddha, a human being who, his uniqueness notwithstanding, was just a man. Nothing special. Ordinary mind. All the clichés. Zen practice is, in fact, a practice of embodying that ordinariness, of getting deeply real, of seeing through each fantasy as it arises—the sweeping, the micro, the feverish and the mundane—seeing its inherent emptiness, and coming to rest in the arms of each fleeting moment, as it is in all its regular luminosity. That is what the Buddha saw and what the Buddha taught, and this is what each Zen teacher teaches. And this is the paradox of Zen, and why Daido, an ordinary, Doublemint-loving, cranky- without-coffee meatball gets to play God in my dreams. I have humbled myself before his Joe-Schmoe beneficence, after all. How could I not expect something big in exchange?

And so, no matter how much we know about our religious teacher’s humanity, vis-a-vis their cheap cologne, or temper, or lack of introspection, we still, in some sense, just like with our parents when we’re little, tend to maintain an element of idealization. Which can help grease the wheels for either deep spiritual connection, or for deep, spiritual confusion.

I am sure there are some super mature, well-adjusted adults out there who are intrigued enough by the nature of the self, to ask to be taught by a Zen teacher with utter clarity of intent. Of course! And we all have our moments, our phases of more or less grown-upishness. But for many of us Zen students, and especially the newer ones, and the more vulnerable for whatever reason, we’ve often already tried every New Age retreat in the catalog, every cleanse on the shelf, and every mid-life reinvention we could muster. We’re desperate. It is usually only after a long and torrid search that we can get motivated to enter the silence, the stillness, the severity of sitting for hours, days, weeks, years on end. Some payoffs are darn quick and aplenty (others are tantalizingly unyielding), and they include a more stable self-confidence, but those early years are tough. And not just physically. There is also the emotional anguish we often enter with, as the result of all kinds of unresolved conflicts and wounds and traumas we didn’t even know we had. We are hungry little babes. Though Zen is not therapy, and even if we know what that means, many of us still want a Good Mommy to attune to us; or maybe we want the Lord-Above to heal us. Add to that the pure sensation that floods our bodies after years of freeze, or addiction, or repression, and, well, some faiths tell their celibate nuns to put a ring on it, and marry Jesus. Other faiths ask us to sit in a room with another person, opening up to the deepest and softest parts of being human, and practice restraint.

Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, author of Zen Mind, Beginners Mind, and a fairly respectable guy when it comes to these things, had something to say on the topic: When a student remarked that this is such a powerful practice, he replied, “Don’t use it.”

It’s often said that finding a teacher is a rare and precious thing. I can vouch for that. I mean, wow. I wake up every morning, and can’t believe I live this life. I have a home, a family, a practice. I feel gratitude to Daido every single day, his picture sitting at my kitchen sink, looking kind of bored, but hey, nothing new there, and at least he’s here, keeping me company. I feel grateful because he was willing to show up in that little pre-dawn, candle-lit room day after day and witness my struggle to pull myself out of the craggy river, and to teach me how to resuscitate myself. He would definitely roll his eyes, or make fun of me, or more to the point, ignore me completely, if he heard me talk like this, or if, God forbid, he read this essay, but I still, almost twenty years later, feel saved. By Daido, yes, but more importantly by the dumb luck of tuning in to a whispery voice that told me there was more to this life than trying to think my way to safety.

And so, setting aside for the moment any legal implications, the trauma of sexual manipulation, the confusion that comes from such a flagrant abuse of power, and any other as-of-yet untold complex and serious consequences of such terrible carelessness, I have my own reason for thinking Zen teachers need to respect the sexual boundary: I would hate to think of a thirst for awakening getting thwarted by the earthly longing to belong to one, very powerful person.

It is true that Daido was there when I was ready to begin on this long and rich and strange road to maybe someday truly meeting myself, and that without him I never would have known how to proceed. But it was my own wish to wake up out of the fog that brought me to him, or, you could say, him to me. And it was, I’m pretty sure, his love of the Buddha’s teachings that kept him out of my way.